Barnabé Monnot

Research scientist @ Robust Incentives Group, Ethereum Foundation.

Research in algorithmic game theory, large systems and cryptoeconomics with a data-driven approach.

A personal history of music

My first musical memory is playing the first song off of The Verve’s Urban Hymns album, the super famous “Bitter Sweet Symphony”, on repeat, when I was five years old. The CD my parents bought had somehow found its way to the oversized boombox I was keeping in my room from time to time. To this day, I have no idea what the rest of the album sounds like, even when it has haunted my iTunes Library since 2009, when I started ripping our CD collection.

Being born in the early nineties, I somehow met and used a large number of music formats and saw in fast-forward the rise or decline of one or the other. Needless to say that music has been a consistent passion ever since I heard the Bitter Sweet “Symphony”, but I find that my personal connection with it has dramatically changed with every successive generation of its interface, from physical supports to digital libraries. Writing a bit about it might be a useful guide to how we experience innovation and how our interactions with music are very much informed by the medium — not an original point by any means, but one that I experienced first-hand.

In my writings I often stress out the importance of systems on user behaviour, and there is a lot to be said of the different systems through which we experience music and culture more generally. This article comes as an exploration of the ways in which this relationship functions, revealed from a compressed history of musical formats.

Be kind, rewind

The day of my musical independence was the day I was gifted a portable CD/cassette/radio player, with a bunch of CD albums — including a Les Enfoirés’ compilation, circa 2001, the French equivalent to Band Aid for the homeless. My personal CD collection grew from there, after buying more albums or singles.

(Singles! We were paying what is now the equivalent of a month of premium streaming service for a two-track CD, when the same format could contain ten times more music and when the second track was always an awful remix of an already not amazing song (hiya, S Club 7 and the Rasmus)).

But perhaps even more treasured than the CD collection was my tape collection. The economic incentive is simple: a pack of 10 cassette tapes was about the same cost then as two singles. The trade-off: I would have to wait until the song I wanted to record was being played on the radio, prepare the tape at the desired recording point and wait until the song stopped playing to physically stop the recording.

The recorded song would thus inevitably start with the last few seconds of the radio station’s jingle or lack its own first seconds if I was too early or too late to record it. And of course, for more synergy, it would be cut short or have the DJ talk over so that the label (which also owns the radio station, by the way) pushes you to buy the clean version of the single. Even then, my imperfect tape recordings helped me save precious euros I would have otherwise spent on songs I ended up growing tired of.

So here I was, waiting for an annoucer’s cue that “Black Suits Comin’” was indeed coming, my finger on the Record button. Side note: my music taste in 2002 had degraded since the Verve. Side note 2: please click on the video link for an instant noughties throwback.

MTV (and MCM, its French equivalent) also shaped my musical evolution in a big way. There I heard Muse for the first time and instantly loved it. At the time it was “edgy”, so it was not playing very often. No problemo: there I am with a videotape and the finger on the Record button. I would record the video clips I thought were cool, throwaway interviews of bands I liked and some live concerts that would sometimes play, sprinkled with old Ghost in the Shell episodes that progressively disappeared as more recordings were made. Technical note: the tapes were rewritable, meaning that you could record something on top of something else, but after a while the quality would seriously deter. Forgetting to rewind the tape or recording from the wrong point would lead Arctic Monkeys to brutally transition into Daft Punk.

Man on Limewire

Somewhere in 2006, after being a Muse-head for a long long time, and while taping the Klaxons’ favorite songs ever as presented on MTV, I heard something that would forever change my music tastes: “Paranoid Android” by Radiohead. This was the first of the even edgier, “underground” songs I would love, and these would definitely not get much airplay on MTV in 2006 (notwithstanding the fact that it was released in 1997). So my tape-powered song-hunting had decisively reached its limit.

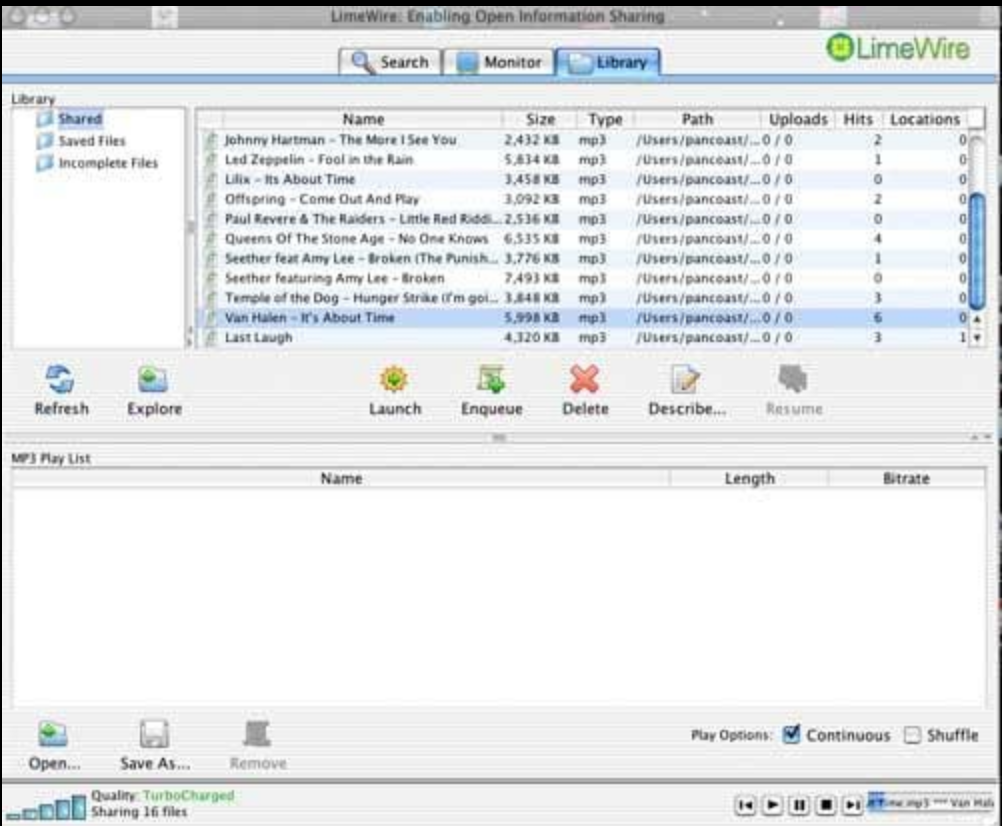

But that year I learned the popular new skill of visiting the most obscure corners of the internet to find mp3’s of my favorite new songs. The element of hunting was still there, when I waited for days on end to download a single track (looking at you, Isobel), but I had virtual access to any song I wanted and it felt amazing.

The other big change was my brand new iPod Video, which to this day I still hold as one of the best appliances I have ever owned, up there with the Nintendo 64. It wasn’t only that I could store my hundreds of new songs and listen to them whenever I wanted, because with a clever paper-based track-listing system I could pretty much do that on my old buddy the CD cassette player and my dozens of tapes. It was also being able to listen to it on my own with the earphones and explore at times very strange music genres that would automatically be shut down by more melody-craving people around the house (Sigur Rós was once described by my brother as a band of whales playing in disharmony and by the time I had reached the outer confines of free jazz and noise music I had to keep a separate playlist of “musical” songs in case the Shuffle on my iPod veered to far left).

Thinking back, I realise how perfectly timed the jump from analog systems to digital files had been for me, but how revolutionary it must have been for any one older than me. People who complained that the mp3 generation has destroyed the value of scavenging obscure record stores for the most niche music genres have obviously never gone through the agony of waiting for the Limewire progress bar to reach 100%, only to find out it was an incorrectly tagged song (For almost a decade I had the wrong version of Autechre’s “Silverside” and only realised it was incorrect after I got the vinyl reissue last Christmas. I much prefer the correct version and suspect the one I had downloaded was an amateur hiding his work to promote it. Not bad.)

No seeds?!? aaarggggg

No seeds?!? aaarggggg

They were right however that peer-to-peer networks were certainly the first step towards a complete individualisation of music. From a collective experience (like tuning in with some friends to some radio show so that we could discuss it the next day, or visiting a record store to ask for a particular album (not something I have done too often I’ll admit)), music moved to a more individual place, because I could now on my own acquire it and listen to it without anyone meddling in the process. Perhaps as a reaction to that I started making “mixtapes” by copying and pasting a few songs in Garage Band into an hour long music mix and sending them out through Mediafire to a few friends. I apologise for some of the dubious choices I made there.

No, scrap that: I fully endorse all of them 😎

Fully digital and fully physical

It now appears that the mp3 era was very much a transitional phase. Even at the time, pirating music did not feel particulary ethical, especially for smaller bands. But paying for songs online was an even worse experience due to the headache-inducing DRMs. The physical aspect of rewinding the tape had translated to making circles with my finger on the surface of the iPod Video, but something felt lost here too.

I spent a few years assembling a good-sized music library (around 100 GB) from various sources, torrents, CDs or tracks paid online. Around the time my hard drive started to be continuously full because of the size of the library, and refusing to outsource my library to an external hard drive due to lag, streaming was quickly gaining traction.

Another phenomenon was happening around the same time: the resurgence of vinyls. This is the format that I had not experienced thus far and only knew from movies, or a book on the 100 best rock albums or my dad boasting of owning all the Pink Floyd and the Who records and my mom those of David Bowie, before they decided to donate them in kind, thinking the format was dead. Around 2008, we bought a turntable and dusted off a few vinyls that did not make it to the donation, including Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) by Bowie and The Head on the Door by the Cure. I bought my first vinyls at that time, the double LP of The Hawk is Howling by Mogwai as well as White Light / White Heat of the Velvet.

I held out against streaming for a few more years, feeling the need to own my music and feeling more comfortable playing a few select albums which I loved rather than a scattered selection of songs algorithmically decided for me. This control was even clearer on the vinyl format, since skipping one song to the next is virtually impossible. So for a time I was happy with downloading most of my songs (legally when I could, such as through Bleep.com where there was no DRM) and “rewarding” artists that I truly enjoyed with buying a vinyl version of the album.

I finally yielded when Apple started Apple Music, which I still regard as a great way to discover a lot more music wrapped in an extremely poor software experience. In an effort to optimize the space in my computer and after a poor backup manipulation on my part, I actually lost most of my 150+ GB library, though most of it has been saved into the Apple cloud and I can still listen to the mysterious old lost tracks of Boards of Canada, when the name doesn’t clash with a more recent track.

But to keep with the theme of how the medium changes my relationship with the music, I now find myself wading more often into the playlists and liking this and that song, playing it for some time and moving on. A significant change too: the default screen on iTunes used to be (for me at least) an alphabetical list of the artists, so I would have to think what do I want to listen to and go and find it. Now the albums I have most recently added to my library appear first, and I find myself thinking less about what I want to listen to and more of what have I last listened to.

To tie it all up together it is worth pointing out that streaming and vinyls could not be farther apart from each other. One is cheap, lower quality, more flexible, the other expensive, high quality and not so flexible. But it is their complete orthogonality that makes it a great value proposition. It has often been said that only major artists can virtually profit from streaming where a large cut is kept by the platform and label, whereas vinyls are where independent artists can recoup most of their costs. It makes sense then that these smaller artists with a dedicated fan base would rely on the latter rather than the former. For the consumer like me, I can enjoy these momentary songs on streaming and keep the timeless ones in a physical format that feels great to play. Although I have no turntable here in Singapore, so I am merely storing them for my future listening!