Barnabé Monnot

Research scientist @ Robust Incentives Group, Ethereum Foundation.

Research in algorithmic game theory, large systems and cryptoeconomics with a data-driven approach.

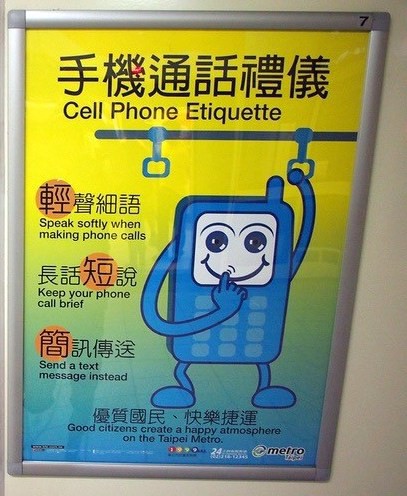

The Taiwan metro etiquette

I have skipped a week in my year of writing but will make it up now with some stray thoughts.

I went to Taiwan in 2015 and really enjoyed my time there. I could tell you about the countless amazing things I have seen and done, my aborted 3-day bicycle trip in pouring rain, the great food and people, but that would take a lot more time! I will focus on a teeny tiny detail that caught my attention and that links especially well to some of my previous articles.

Social norms and values are always a tough subject. Economists usually favour an approach that is based on system efficiency or some definition of equity. Policies tend to care more about order and implementation. A common point is that both are known to disregard actual human behaviour. I have brushed on this topic when I wrote about pedestrian overhead bridges, which are the physical embodiment of a certain idea of efficiency (a car-driven one, in short) as well as a complete design failure in a lot of cases — to paraphrase a famous quote, by an architect I cannot remember the name of (help me! 😕), overhead bridges are great at one thing: providing shade to the people who jaywalk under them.

So the Taipei metro etiquette caught my eye for its pragmatism. Here it is:

Picture taken from http://www.yamventures.com/top-tips-before-planned-trip-taiwan/

Picture taken from http://www.yamventures.com/top-tips-before-planned-trip-taiwan/

It is certainly futile to demand that people not use their phones in the train and if you have taken public transport (who hasn’t?), you have seen people having conversations interrupted by the poor signal underground — ‘Hello? hello??’. Even if you do demand that, enforcing a ban would be especially awkward, since unlike smoking, the inconvenience is either limited or it is an actual obligation for the caller (in an emergency, say). So it falls in the grey zone of customs and traditions rather than a penal issue.

Taipei metro asks for a different thing: if you do make or take a call, be mindful of the people around you. It recognises that yes, people do take calls on public transportation. But if they do, they should have in mind to minimise the inconvenience of the people around.

Though I have no data to prove it, I have the intuition that it is actually a better policy. Compare with a big red sign “No phone”: it is self-defeating, because every folk in the train car knows it is a possibility that some other person might make a call and knows that it cannot be enforced either. So the rule stands but is in effect useless, adding to the “interdiction fatigue” present in many places (if you have seen one of these “Singapore is a fine city” t-shirts, you know what I am talking about). Worse: once you have crossed that bridge of actually making the phone call, what keeps you from having a loud drawn-out conversation? You already disregarded the rule, for good reason: you knew it was anyway possible the rule might be disregarded by someone else and who enforces it anyway?

So instead, if you are taking a phone call and being obnoxious about it, the rule is: you should observe a good etiquette while doing so. In the mind of the other commuters, you may become “the person who disregarded the phone etiquette” (bad) instead of “the one folk who was having a conversation this morning on the train” (expected). Because you are a self-conscious animal, you are also modelling the thinking of the people around you in your own mind, and perhaps your behaviour is more likely to change in the first case than in the second.

“This is really nitpicking!” Yes, a bit, I’ll admit. There are also several unchecked assumptions in there, but my point was more to reiterate on the idea that systems and policies need to take a look at human behaviour. There are also dozens of things we need to fix with public transportation, such as accessibility, safety (which if you believe the Spruce, is not one reason people do not use public transportation, LOL) and the general economics of it.